As readers of this blog already know, the novel I'm currently writing is about yet another cook, Bartolomeo Scappi, who was a Renaissance chef to several cardinals and...

Renaissance chef (and character in my second novel), Bartolomeo Scappi, wrote a cookbook that was released in 1570 and was one of the most reprinted cookbooks over the next two hundred years. One of the most wonderful things about his cookbook, The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi, is that it is still very accessible today. There are exceptions, for example, modern audiences would not be interested in some of the meats (hedgehog or blackbird anyone?), and many of the items are not readily available or, like his feathered peacock, are too elaborate too make.

Fortunately, many of his recipes are are still pretty easy to figure out. Like this one for braised beef:

2.11. To stew a loin of beef in an oven or to braise it.

Get a loin of beef as good as was said before, along with some of the fat and a little of the backbone. After it is cleaned of its membrane, splash it with wine and white vinegar, and sprinkle it with pepper, cloves, ground salt, cinnamon, ginger and with coriander or else fennel flour. Let it sit under pressure in an earthenware vessel for four hours with a little Greek wine or malmsey, must syrup and rose vinegar. Then put it into an oven in the same vessel with that same mixture, adding in a little beaten pork fat and thin slices of prosciutto. When it is half cooked, having turned it over a few times, you add prunes and dried visciola cherries into it if it is winter, in summer, though, you can put in the fresh fruit. When it is cooked, it is served hot with the same things and the broth over it. In the same way you do it braised.

My husband loves to cook and tinker with new ingredients so he was excited about the challenge of helping me figure out this particular dish. It's not going to be the most economical recipe, but for food lovers or history buffs, it's worth trying. It's a seriously delicious if not decadent dish. Some of the ingredients are not ones you would find normally on your grocery shelf but with the Internet, are still fairly easy to procure. Let's go through the more complicated bits of this recipe.

The beef loin in question here would likely be the ENTIRE beef tenderloin. That's tricky for audiences today primarily because of the size and the cost. Renaissance chefs also had a different perspective on flavor and cooking in general (and with everything cooked over a fire it added a whole new level of complexity). Tenderloin is one of the choicest cuts of meat and to braise or stew it would detract from its flavor and probably make it tough. Cuts of meat that would work better in this recipe would be large tough cuts of meat with some fat on them, such as roasts, ribs, brisket or shanks. The first time we made this we chose an eye roast but it didn't have enough fat and was more tough than tender (it could also be that we should have shaved off a lot more of the cooking time). We decided on a short ribs the second time around.

Fennel pollen is seeing a renaissance of its own lately, cropping up in new fangled dishes at restaurants all over the country. Used for centuries, it's the pollen from the flower of fennel plants. You can snag some at gourmet grocers or on Amazon. You can dust it on pretty much anything, meats, cheeses, use it in sauces, etc. Or, as Scappi suggests, just use coriander, which most groceries sell.

Malmsey is a type of Madeira (a sweet wine similar to sherry) made from malvasia grapes. Madeira as a rule tends to not be that expensive, but Malmsey tends to be on the higher price side of the madeiras, coming in around $25. The good thing is that you can drink it smooth as a dessert wine, or use it in sauces. It will keep at room temperature for a very long time. If you can't find the malmsey or don't want to spend as much on the wine, pick up regular Madeira. You can also use red wine but be warned it will taste completely unlike what Scappi likely intended.

Must syrup is essentially pressed grape juice that contains seeds, stems and skins of the grape. Must is usually cooked and reduced into a syrup which can be used in cooking. While not easy to procure everywhere, you can still find the Italian vin cotto, a syrup made from grape must, or in some cases from figs. It can be found in gourmet Italian groceries or also on Amazon. It's amazing in sauces, drizzled on salads and on cheese or over roasted meats.

Rose vinegar isn't common today but you can find a modern version on Amazon, or you could combine white wine vinegar and traditional rosewater (found in Middle Eastern groceries) for a decent modern equivalent. Rosewater is an increasingly common ingredient in pastries and cocktails so it is easier to procure than in the past. Don't worry, when it cooks it blends very nicely. You can probably also find it in Middle Eastern or Greek markets.

Visciola cherries are probably the closest cherry we have today to what cherries in Scappi's time would have tasted like. Today's cherries are sweeter than they would have been in the Renaissance. That said, the differences are bound to be small so don't sweat it and get what you like.

Pork fat was likely just fatback, which is easily procured at a quality butcher, but you could also use bacon, as we did, or lardo (different than lard, it's cured fatback). Fatback is the pure fresh cut of fat from the pig, not the smoked, cured meat of bacon or lardo, but for modern purposes and tastes (and the small amount needed), bacon will do.

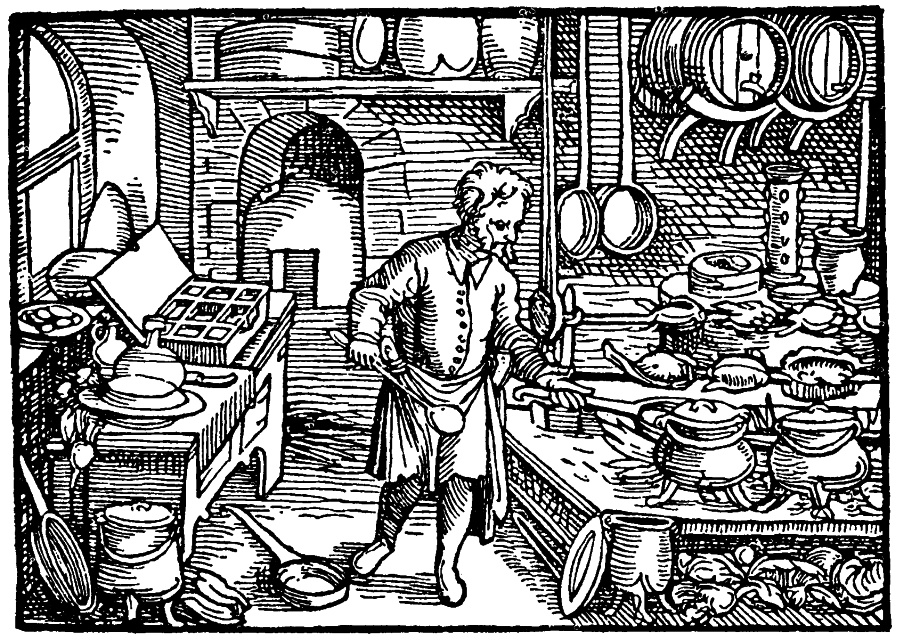

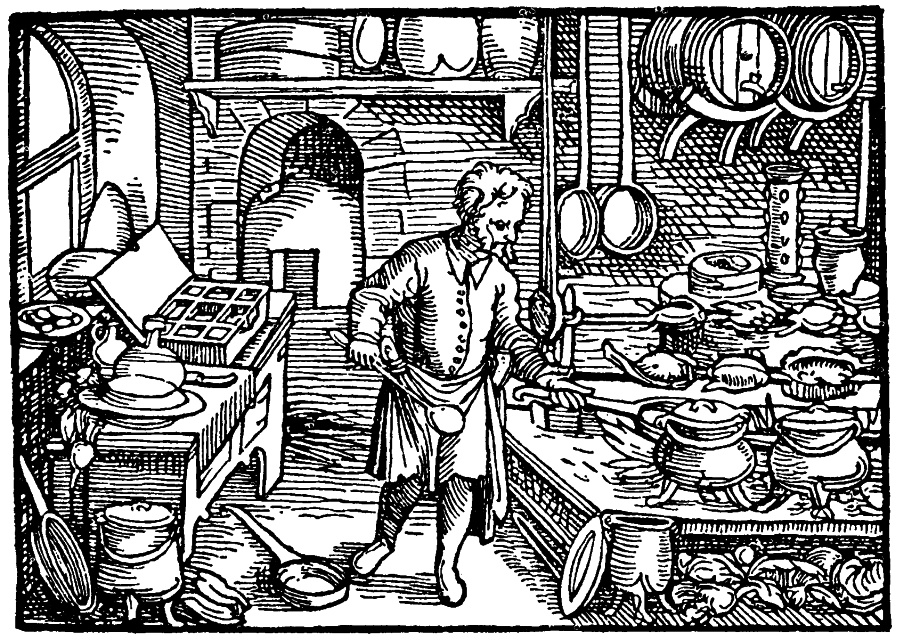

Scappi would have cooked this recipe in a earthenware dish which was covered with a bell-shaped top,

similar to the one pictured here from his cookbook. For modern audiences, a dutch oven will do just fine.

Or, if you don't have a dutch oven, tin foil is a handy substitute. If you have a pressure cooker, that would work too but you might want to adjust cooking time.

There are a lot of ingredients, but that was typical of the day. You'll notice it's primarily a lot of spices. Overall it's a very easy recipe to make though, so don't feel intimidated by the length of the ingredient list!

Note that all the amounts, the time to cook the meat, etc., are approximated since as you can see from the above, Scappi didn't give amounts. Feel free to adjust as needed.

Serves 4-6 people

2 lb beef short rib

1 teaspoon pepper

1/2 teaspoon cloves

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon chopped fresh ginger

1/2 teaspoon coriander or 1/2 teaspoon fennel pollen

3/4 cup Madeira malmsey wine

1/4 cup vin cotto

1/4 cup rose vinegar (or 1/4 cup white wine vinegar with 2 tbsp rose water)

2 strips of thick-cut bacon

2 strips of prosciutto

1/2 cup of prunes, or pitted plums, cut in half

1/2 cup dried cherries or pitted fresh cherries

Buon Appetito!

Want more Renaissance recipes! Check out my free digital cookbook!

As readers of this blog already know, the novel I'm currently writing is about yet another cook, Bartolomeo Scappi, who was a Renaissance chef to several cardinals and...

.jpg)