Back in 1987, archaeologists discovered a treasure trove in a floor drain of the Roman Forum. This "treasure" was 86 loose teeth, all intact but with cavities in various...

This article first appeared in the inaugural issue of the beautiful food history publication, EATEN Magazine. If you love food and love reading about the fascinating history of food, definitely snag a subscription...you won't be sorry! The photos of the cake were taken by Valerio Necchio.

When I first embarked upon writing my novel, FEAST OF SORROW, about the ancient Roman gourmand, Apicius, I knew I would require a vast amount of research to understand everything I could about the food of that era. I wanted to understand the difficulty of preparation, the nuances of flavor and how foods might pair together. That meant I needed to, quite literally, get cooking.

Most of the very ancient Roman recipes that have been left to us tend to be a short list of ingredients and in some cases, a rudimentary and usually incomplete set of instructions. The ancient Roman cookbook, Apicius, is full of these sorts of recipes. A home cook of today would have no idea where to begin when it came to extrapolating these vague lists into something edible. I was relieved to discover that others had already done much of this interpretation for me. I began my cooking research by trying dishes found in cookbooks by historians such as Andrew Dalby, Ilaria Gozzini Giacosa, Sally Grainger, Mark Grant and Francine Segan. But it wasn’t long before my husband and I were testing out our own interpretations of foods such as roasted mushrooms, sweet and sour dill chicken and dessert treats like fritters.

One of the foods mentioned several times in my novel are honey cakes, which are offered up to the gods in thanks. I was intrigued by the idea of these cakes and how I could recreate them today. What were their origins? Why did the ancients offer up cakes to their deities?

If any of the ancient myths are to be believed, the gods of ancient Greek and Roman antiquity loved a bountiful meal. The stories left to us by Ovid, Herodotus, Virgil, Homer and others are ripe with stories of grand feasts enjoyed by the gods, or the gods meddling in mortal banquets such as the feast of King Midas in which all of the food tragically turned to gold. In fact, for centuries beyond ancient times, the wedding celebrations of Cupid and Psyche and Peleus and Thetis have been common artistic subjects for vases, frescoes and paintings of the great masters.

The feasts on Mount Olympus were similar to those enjoyed on earth save in abundance, superior taste, luxury and perhaps the addition of the divine ambrosia. A traditional ancient Roman banquet would have begun with eggs and ended with fruit, and the final course was often accompanied by sweet desserts such as cake.

Cake is a dish that has been around for thousands of years, and was enjoyed by the ancient Egyptians well before the Greeks and Romans had their fill. Paintings in the tomb of Pharaoh Ramesses II, who ruled from 1304 to 1237 B.C.E. show what archaeologists think might be a type of folded honey cake, likely made from flour, eggs, honey, dates and nuts. The Egyptian specialty feteer meshaltet, which is a thin folded pastry (and might even be the precursor to the French croissant), is descended from these cakes.

One of the first printed recipes for honey cake appears in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae, published in Greece in 180 B.C.E.. It is called Enkhytoi and the book describes it as a flat, molded cake made from honey, fine flour and eggs. Like many recipes of the time there were no proportions listed, but modern recreations of these cakes show us that the consistency is that of a sponge cake.

Birthday cakes are also ancient, as the first century poet, Ovid, wrote about in his elegiac letters, titled Tristia, which bemoan his exile to Pontus (now part of modern-day Turkey):

Thou awaitest, I suppose, thine

honour in its wonted guise: a white robe hanging

from my shoulders, a smoking altar garlanded with

chaplets, the grains of incense snapping in the holy

fire, and myself offering the cakes that mark my

birthday and framing kindly petitions with pious lips.

Ovid uses an interesting turn of phrase within this passage--the offering of cakes to mark his birthday. While he himself likely enjoyed some form of cake as part of his celebration, it was the idea of giving an offering to the gods that is important in this letter.

In nearly every religion food plays an important role when it comes to worship. It began as sacrifice—giving a gift to the gods to incur divine favor, give thanks, or avoid retribution. Lesley and Roy Adkins, in The Dictionary of Roman Religion, tell us “a food offering might be shared between the gods and the people in a sacrificial feast, or the food might be given entirely to the gods by burning it all.” Animal blood sacrifices were common, but also gifts such as oil, wine, incense, honey and...cakes.

When it comes to ancient cakes, the only sweetener they had was honey. Honey cake is still a traditional food for many cultures today, particularly in Jewish culture, where honey cake (called Lekach) on Rosh Hashanah is as ubiquitous as fruitcake on Christmas.

The ancient Roman cookbook, Apicius , (named for the wealthy first century gourmand), has several sweet (dulcia) cake recipes that are possibly centuries older than the third or fourth century compilation. Historian Sally Grainger translates two of them thus:

Apicius 7.1.4 dulcia piperata

Pound pepper, pine nuts, honey, wine, passum, and rue. Add to the mixture pine nuts, nuts and boiled alica (polished spelt grains). Add chopped roasted hazelnuts.

Apicius 7.11.5 aliter dulcia

Pound pepper, pine nuts, honey, rue, and passum. Cook with milk and tracta (this was a thin pastry that the ancient Romans sometimes crumbled into dishes for starch). Cook the thickened mixture with a little egg. Serve drenched in honey and sprinkled with pepper.

When interpreting the Apicius sweet cake recipes for a modern audience, I found that the combination of these two cakes make for a dessert more palatable and familiar to us today. However, I discovered that I needed to make some exceptions to the original recipes. For example, the bitter herb rue is not easy to come by in all regions, so it is substituted with another ancient and sweeter spice, coriander. Additionally, modern cooks have leavening agents at their disposal and it is far easier to use them than making some form of sourdough starter. But I also wanted to stay true to the era. With the exception of the baking powder, all of the ingredients in this recipe would have been available in some form to the ancient Romans.

A few notes on some of the ingredients:

Flour - Spelt and semolina were the most common grains used for flour in ancient Rome, although flour from rye and oats were also found. Soldiers and plebians would have eaten bread made from barley or perhaps acorn flour. The ancient Romans did have white wheat flour, which was only available to the very wealthy. The darker breads were not preferable by the rich, and Pliny writes in his Naturalis Historia 18.11: "The wheat of Cyprus is swarthy and produces a dark bread, for which reason it is generally mixed with the white wheat of Alexandria." Therefore, home bakers should not feel guilty thinking that white flour might not be authentic in this recipe.

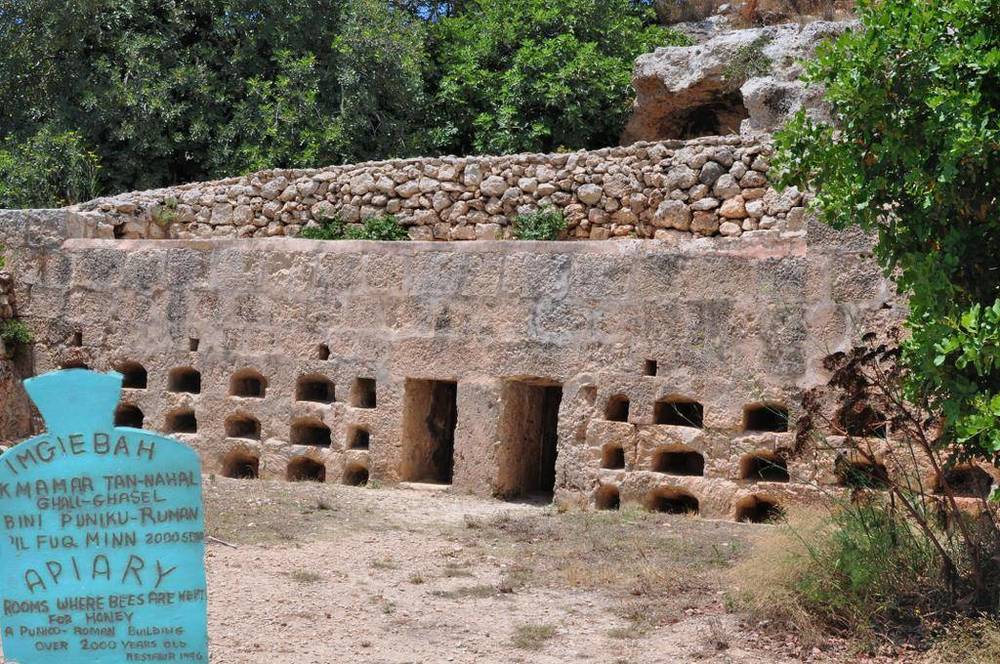

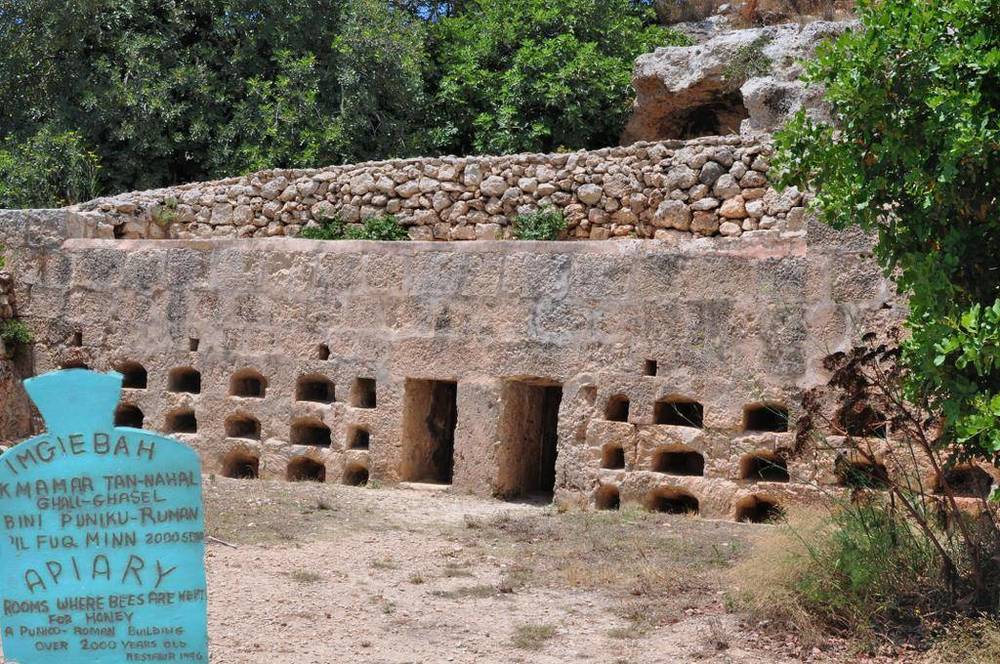

Honey- Honey was a regular staple of the ancient Roman diet. Keeping bees was a respected art and apiaries were elaborate and large in many places. One such apiary is still viewable in Malta, a little island off the coast of Sicily. The apiary was huge (it would have accommodated over 100 hives in its time) and enabled the beekeeper to go behind the hives and easily remove the honeycomb from slats in the wall. Honey from different locales tasted differently, of course, depending on what the flora was in that area. Horace tells us in his Epistles that the bees loved thyme and in his Odes, he praises the honey around the area of Tarentum, in Apulia in Southern Italy. Andrew Dalby, in his fascinating book, Empire of Pleasures, tells us that Sicilian honey was some of the best in the ancient Roman world. Spain, then called Hibernia, was also a major source of honey.

Pine Nuts – If you aren’t fond of pine nuts because of their aftertaste, look for Turkish or Italian pinenuts in specialty or gourmet stores (more expensive but worth it). Chinese pinenuts can impart a waxy, metallic taste. Store your pinenuts in the fridge for up to three months, or the freezer up to nine, to prevent them from going rancid.

Soda - Sodium bicarbonate was used by the ancient Egyptians for nearly three thousand years before the recipes in Apicius were written down, but used primarily for treating wounds, preserving meat and as a cleaning agent. Leavened bread and cakes were made from natural yeasts like a sourdough starter. Today, of course, for ease of use, we use baking powder and soda as leaveners.

Wine - For this recipe, a sweet white raisin-based wine is preferred, for example, the Greek Kourtaki Samos Muscat, or an Italian passito wine, but any very sweet white wine will work. Pliny and Columella both describe raisin wines in their writings.

Fresh plums, apricots, apples, figs or grapes would all be perfect ancient Roman accompaniments to this cake.

Fresh plums, apricots, apples, figs or grapes would all be perfect ancient Roman accompaniments to this cake.

Ancient Roman Honey Cake

DULCIA PIPERATA

Serves 8-10

PREPARATION

If you try this recipe and want to try your hand at other ancient Roman recipes, check out my free digital cookbook, the companion to my novel, FEAST OF SORROW.

Back in 1987, archaeologists discovered a treasure trove in a floor drain of the Roman Forum. This "treasure" was 86 loose teeth, all intact but with cavities in various...

This is an ancient cracker recipe from Athenaeus, a rhetorician and grammarian who lived in Rome in the 3rd century AD. This recipe is a delightful, snacky...